Appendix - Hexmvc Events

Andy Bulka,

March 2012

Back to main HexMVC Pattern.

On Eventing

Eventing is up to you to implement any way you like. You need to be able to broadcast ‘events’ which cause methods to be run on an arbitrary number of observers. The broadcaster is ignorant of the exact identity of the observers. Its the observer pattern.

A lightweight synchronous, eventing system

I recommend a lightweight synchronous, eventing system / observer pattern that is based on method calling on objects. It

- does not require event objects

- does not require registrations of interest

- does not have complex if then else statements figuring out what to do

- does not need classes to implement subject or observer functionaltiy

All you need is a multicast object type, which holds an array of interested listener objects. When you call a method on that object, the method is called on all interested listener objects. The method name you are calling is deemed to be the ‘event’.

In the following example, observers is a variable of type ‘multicast’.

e.g.

observers += obj1

observers += obj2

observers.NOTIFY()

The call to observers.NOTIFY() will cause

obj1.NOTIFY()

obj2.NOTIFY()

I am assuming a dynamic language like python or ruby here. Conceptually, the observer being called must adhere to some expected interface, so that the method/event being called actually exists! In a dynamic language you don’t need an interface - it can be a convention - ‘duck typing’.

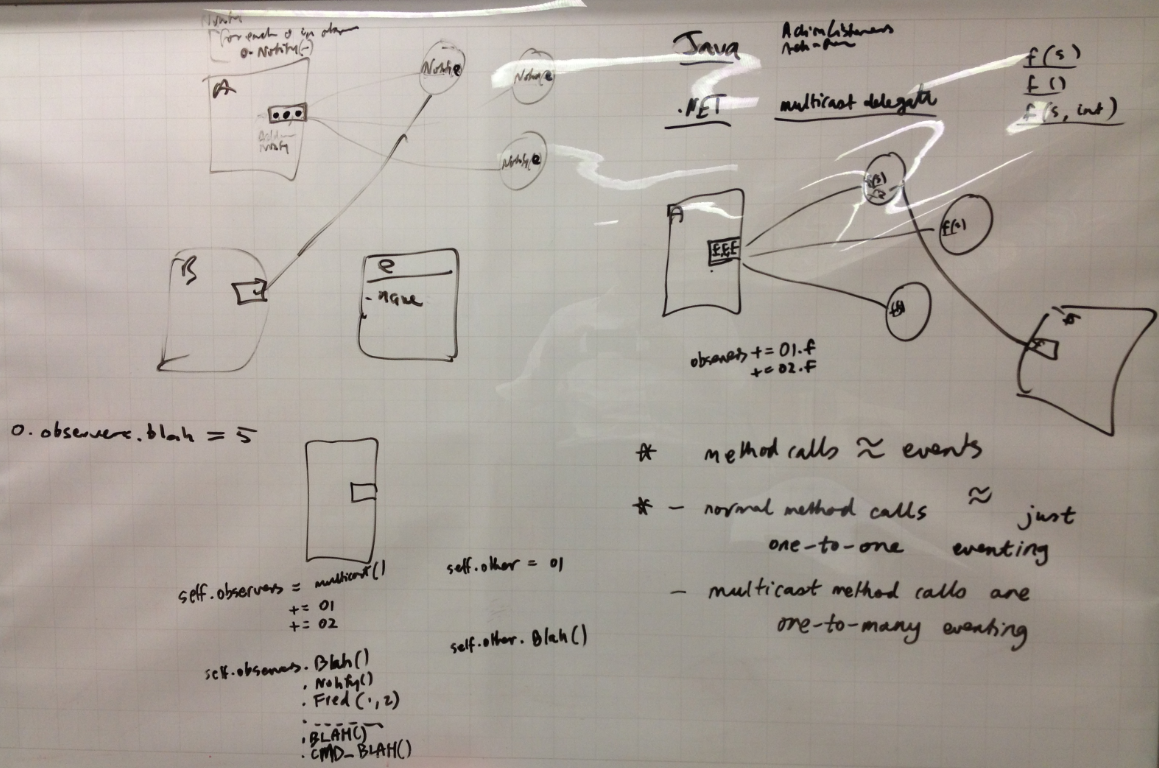

Dependency Injection - one to one, one to many

One insight at this point might be that wiring up one-to-one pointers and wiring up one-to-many pointers/observers in this way are just variations of the same thing.

When you wire up your objects to point to each other you are doing dependency injection - as long as the objects are not instantiating instances of the objects they are pointing to themselves, and the injection is done from ‘outside’. The objects being injected are thus depending on an abstraction or interface - which is injected later.

Similarly, when you wire up the observers of an object, by adding them repeatedly using += to a list in a multicast variable, you are also doing dependency injection, except with a multicast flavour.

Its all just wiring. Its just that some wires are one-to-one and others are one-to-many.

Eventing is just method calling

Eventing becomes just method calling on multiple objects

This leads to another insight. Eventing is just method calling. Objective C I think sees the world in this way. And Ruby. Possibly this is obvious to some people and some languages, but when you do eventing this sort of lightweight multicast technique, it becomes much more obvious.

Whether a method call on an object results in one method call or many method calls is irrelevant. You could say that calling a method on an object is the same thing as a single event call.

observer = obj1

observer.DoSomething()

vs

observers += obj1

observers.DoSomething()

If you adopt an meaningful name and perhaps an uppercase naming convention on method names which are being called in an event style, then it becomes even more obvious e.g.

observers.NOTIFY_SOMETHING()

When a method is in uppercase, it looks more like an event, to me. So that’s why I do it. When I see a method in upper case I know that it is being called as part of an observer eventing pattern call. In other words calling methods in this way, this IS the way you broadcast events.

It nice that eventing and method calling become the same thing because you don’t have to learn anything new. You can pass information in parameters just as you would with a method call.

Its all just method invocation, which is all just eventing - and vice versa - in a sense. As long as its all hooked up using the principles of dependency injection, which insists on depending only on abstractions/interfaces.

Its a neat symmetry that lightweight eventing, dependency injection and adapters satisfying interfaces all work together within the HexMvc framework. The high level architectural concepts and the low level implementation idioms are similar, forming a powerful, cohesive, interrelated yet simple architecture.

Advanced Footnotes on Eventing

Eventing vs. Method Calling

In the end, whether an event object is being created and passed to an eventing framework - or whether a piece of code has the knowledge to call a particular method - its all ‘knowledge’ and thus a ‘dependency’. Knowing what sort of event to raise or register is no less coupled than simply knowing what method to call.

This argument assumes that you have sufficiently decoupled things by using interfaces and abstractions. For example, some degree of decoupling occurs when you call methods via eventing, since the caller/raiser doesn’t know what particular objects are ultimately being called. The same level of loose coupling can also be achieved with ‘mere’ method calls, as long as the object whose method you are calling has been abstractly injected, so that the caller has no idea who is implementing that interface.

The benefit of a multicast method calling approach over an eventing approach is that it is simpler and avoids too much syntax, declaration, duplication and registration etc. If you already have a nice eventing system and are happy with it, then by all means use it.

Functions instead of objects

A single or multicast notification approach can be done with references to functions (as opposed to references to objects). You can have a single reference to a function or a reference to an array of functions.

Whilst lists of functions are usable in some situations, I haven’t really thought about eventing in HexMvc using functions only - because it seems to me that functions only give you one shot at calling a method, whilst having a list of objects that implement an interface, gives you an unlimited set of methods you can call on those objects.

This sort of eventing will probably work ok in C# and other .net languages too, using delegates - though there will be the usual type declaration dance needed. And note that I am assuming the multicast object points to a list of objects, not functions - not sure if this is possible in .net delegates?

Synchronous vs Asynchronous

A synchronous call from view to controller to model, and an immediate calling chain back again in order to construct an immediate response object - this is web mvc. A partial downside of this approach is that the model doesn’t get a chance to broadcast updates to other sub-systems of the app. If we allow the opportunity for the model to broadcast a message, then other sub-systems like GUI views (not web view related) can update with information. In other words, a controller setting info on a model silently is a bit limiting - a controller that sets info on a model via a model adapter will trigger other update notifications, which can be a good thing.

All based on synchronous calls - even if it looks like eventing. Not addressing asynchronous, except in the limited context of server threading.

Observer based Eventing

A bit of history on Observer based Eventing

This is a bit of a tangent, and may form part of another talk.

Regular observer pattern

With the regular observer pattern, you have a ‘subject’ object which contains a list of observer objects. The subject then loops and calls a particular method on all these observer objects when a notification is required. That’s the basic idea. You can pass paramters in the notification call, incl. strings to tell the observers of different actions to take. Optionally add some type safety if you like, to ensure both observer and and ensure both observers follow some interface (to ensure the observers have a OnNotify() method and to ensure subjects have an AddObserver(o) method etc. Optionally even add some functionality in a subject base class so that your looping NotifyAll() method only has to be implemented once.

Implementations

Java

Java’s ActionListener with their ActionPerformed methods is essentially the Observer pattern, built into the language/libraries. It might be a bit cumbersome for normal usage in your app - being very GUI widget centric, but the essential point I want to make is that observers are lists of objects not functions.

.NET

C# and .NET introduced the idea of observer pattern broadcasting using multicast delegates, which are lists of typed functions. A benefit of this approach is that it doesn’t matter what the observer’s class is or what interface an observer implements - all that matters is that the functions which are added to a subject’s observers list follow the same method signature. The list of oservers is a multicast delegate object, also pretty much the same thing as an event. Thus observers hook into some subject’s event in this way.

A possbile downside (or upside, depending on your point of view) of moving from lists of objects to lists of functions is that if there are 10 events you need 10 events on the subject, and 10 functions on each observer. With the regular observer pattern, you need only have one subscription by an observer, then the observer has to figure out what out of the 10 things happened, usually by a string passed as a parameter e.g. observer.Notify(what) and then an if-then-else statement to perform the relevant code.

Birger’s thoughts on ‘multicast’ in .NET

I sent an email to my colleague Birger who is an expert in .NET

Hi Birger,

I’m wondering if I could ask you a .NET question that would add some colour to my talk next week. I’ll be talking about observer pattern and possibly mentioning using .NET events / multicast delegates. Is there something in .NET that allows for lists of OBJECTS (not functions) to be += to some sort of delegate object so that I can invoke a variety of different functions on that list of objects?

Im looking for something built into .NET that would work like my python example below where ‘observers’ is a variable of type ‘multicast’ and holds a list of OBJECTS.

e.g.

observers += obj1

observers += obj2

observers.NOTIFY()

The call to observers.NOTIFY() will cause

obj1.NOTIFY()

obj2.NOTIFY()

Thanks for any thoughts,

Cheers,

Andy

Birger’s response

Hi Andy,

There’s nothing like you describe built-in that I can think of. The preferred way is to use delegates, at least in UI code. However, I can think of three or four things you may want to consider…

-

There’s nothing preventing you from implementing the observer pattern the way it would be done in Java. (e.g. adding an object implementing the ActionListener interface to a button: http://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/uiswing/events/actionlistener.html

-

Unlike Java, C# supports operator overloading. You can’t explicitly overload the += operator but you could overload the + operator where your Subject is on the left hand side, your Observer is on the right hand side and the return value is the same type as your Subject. Then effectively+= would do what you want. C# won’t allow your Subject to be an interface because operators are essentially static methods and interfaces don’t allow you to define method implementation (and Microsoft have decided against supporting this via extension methods). Your Subject would have to be an abstract or concrete class.

-

Since .NET 4.0 Microsoft has included generic IObserver and IObservable interfaces.

The IObservable interface has a Subscribe method which does what I think you want the += to do. There is no Unsubscribe method. Instead the Subscribe method returns an IDisposable object which when disposed (by calling Dispose) should unsubscribe the Observer. The IObserver has three methods: OnNext, OnError and OnCompleted. OnNext is the standard notification method, OnError is to notify the observer of exceptions and OnCompleted would be the last event (e.g. when the Observable has finished iterating through a collection, reached the end of a file or the UI object generating the events has been disposed). -

WPF has something called ObservableCollections. I don’t know much about WPF but this would be more of a library feature than a language feature and it would be tied to WPF UIs.

Hope my thoughts can help with your presentation.

Cheers,

Birger

Python Multicast

I contend that the python multicast class is another even better way to do eventing.

This multicast object technique is not a feature of python but can be done in any dynamic language e.g. Ruby.

In the following example, observers is a variable of type ‘multicast’.

e.g.

observers += obj1

observers += obj2

observers.NOTIFY()

The call to observers.NOTIFY() will cause

obj1.NOTIFY()

obj2.NOTIFY()

In this implementation the subject has a list of objects - so its more a traditional observer pattern implemnentation. What makes it unique is that the looping/broadcasting code is built into the multicast object, so there is no need to worry about subject base classes or subject interfaces. All you do is create a multicast object as a variable/property of your class and you are good to go.

The other benefit of this implementation is that observers simply add themselves to the multicast object and the calls into the observer happen as normal method calls. If you call observers.FRED() then all observers which have a method FRED() will have that method called. You can have any number of method calls, and this doesn’t have to be agreed upon in advance with interfaces etc - though you could add that layer of type safety if you really insisited.

Also the method calls can take parameters. Eventing just becomes method calling - same technology, same techniques - nothing new to learn. If your observer doesn’t declare a particular method then it will be silently skipped (depending on the nuances of your implementation, you could change this default behaviour).

The big picture

Notice that when we have a normal reference to an object e.g. self.other = o1 you perform a method call on that other object with the usual self.other.Blah().

Notice that in our multicast situation, you have a reference to a number of objects e.g. self.observers += o1; self.observers += o2; you perform a method call / event broadcast on those other objects with self.observers.Blah().

Its the same thing. Singular or plural. Method calling and eventing. It all collapses into the same thing.

What this means is that

- method calls are just events

- normal method calls are just one-to-one eventing

- multicast method calls are one-to-many eventing

Ruby implementation

The python implementation looks like:

http://code.activestate.com/recipes/52289-multicasting-on-objects/

the core of which is:

def __call__(self, *args, **kwargs):

Invoke method attributes and return results through another multicast

return self.__class__( [ (alias, obj(*args, **kwargs) )

for alias, obj in self.items() if callable(obj) ] )

A ruby implementation might be http://codepad.org/6tgNK8Fz

I haven’t addressed the multicast attribute access yet. And I haven’t addressed the return values issue, though I don’t see how a multicast can return values - unless some sort of list of return values is constructed and returned.

# Beginnings of a 'Multicast' class to multiplex messages/attribute requests

# to objects which share the same interface.

class Fred def hi puts "hi from Fred" end def count n

n.times { |i| puts i } end

end

class Mary def hi puts "hi from Mary" end def count n

n.times { |i| puts i+100 } end

end

class MulticastObjects def initialize

@objects = \[\] end def add(o)

@objects << o end def method\_missing(meth, \*args, &block)

@objects.each do |o|

o.send meth, \*args, &block end end

endobservers = MulticastObjects.new

observers.add(Fred.new)

observers.add(Mary.new)

observers.hi

observers.count 5

puts "done"

output

hi from Fred

hi from Mary

0

1

2

3

4

100

101

102

103

104

done

Back to main HexMVC Pattern.